The dynamic nature of power in the father-son relationship

Open your heart

The anti-hero protagonist of God of War (GoW) is probably one of the best video game characters ever written. The character arc that has been developing since its inception has been one filled with meaning derived from being a warrior, a killer. A Spartan, Kratos moves from being a mere boy to leading a spartan army. His purpose is ever moving, while the strings are being moved by the gods. In actuality, Kratos hardly has any freedom in what he does; this led him to killing his own wife and daughter, a deceit planned by then God of war Ares. His identity, state of being & movement is now directed with hatred and need for vengeance. Eventually he finds Athena who serves as his guide in his journey to avenge the death of his wife & daughter. But Athena too had her own intentions- to seek the power of hope for herself. God of War III ends with Kratos destroying the power of hope himself.

This is not necessarily about the re-telling of Greek mythology as shown in the GoW games, but rather focuses on the consistent power struggle that children have with their parents as authority figures. For this, I am focusing on the relation between Father and Son, and the power struggle that ensues. In GoW, Kratos learns that his father is the Greek god Zeus. By the end of GoW, Kratos kills his father Zeus- in an act of vengeance filled with hatred, anger and mistrust towards the gods. Before Kratos, Zeus had killed his own father Cronos to become the King of Olympus. It was prophesized that Cronos will be overthrown by his own son, and in order to prevent that prophecy he swallowed every child his sister-wife Rhea bore him.Thus the need for and to maintain power continued. A cycle of sons killing their fathers started and would continue.

GoW (2018) is probably one of the greatest games to have ever be created. The character arc of Kratos undergoes a drastic change as we see him in Midgard, as we are taken to Norse mythology. He has a son named Atreus, and at the beginning of GoW (2018), we see him and Atreus mourn the death of his wife. The story is immersive, moving and feels deeply personal because from being a God of war filed with vengeance and hatred, throughout the game Kratos is learning to be a father. Something that every reviewer has pointed out is that Kratos goes calling his son “boy” to actually calling him by his name.

Why am I, a therapist who clearly games, has decided to write about a game, what has it got to do with anything? I wish to take the themes of GoW games to look into the dynamics of power, authority, and change. I am aware that what I might have to say has already been done so, yet I wish to look into the contemporary nature of the father-son dynamic. Needlessly to say, my thoughts are not all-encompassing.

I do not know what it is like to be a father, but I do know what it is like to be a son. In the larger theme of patriarchy, fathers are supposed to be stoic figures who protect and provide. They are expected to be strong-willed, decisive, and brave. Sons are expected to fill the shoes of their father. While no one asked either what they wish to be, or do. My father likes to say- “one day you will be a father, and you will understand what that’s like.” My male friends have had similar experiences, and we have come to realize that we need not discard that completely. Another fundamental question that arises is the assumption that someone will be a father- almost like a prophecy that is bestowed upon. When that prophecy is fulfilled, we shall finally understand the struggles of fatherhood. I think about the lack of space of freedom & being in this. You are expected to carry forth your bloodline, otherwise the generation ends with you. While you are expected to do so, the above patriarchal introjections becoming more and more real. Underlying all of this exists power. The power to create, raise and parent a child. While paternal uncertainty is a reality, mostly subverted via monogamy, the father tries their best that the son turns out to be like them. The anxiety of paternal uncertainty might be compensated via the power influences that the father has upon the child. The word of the father is the word of God. The son is appreciated when he is obedient, and dismayed when defiant. Here, it is important to acknowledge that the father is also a son. The father’s father might be living or dead, and either might have its own consequences into fatherhood. The grandiosity of the word ‘grandfather’ is hardly ever lost. What does it mean for men of three generations to co-exist? Who yields most power? Older people tend to take on the role of children as they grow, relying heavily on their own children for care and support. The stoic father becomes frail. The brave father needs support, and the breadwinner is now dependent. Sons who have fathers who are old and have their own sons have multiple roles to play. Imagine taking care of your son, and also your older father who has also become like a child- the intrapsychic conflict of this father in between generations is hardly ever paid heed to.

On the other hand, a father who has lost his own father might mourn the loss of his stoic figure, while simultaneously moving towards his own supposed valour. There are many realities that exist, someone might not have had a father, others might have had a symbolically absent one, and some might even be estranged. Whatever the reality, it is hardly plausible to deny the dynamic power that comes from being a father. An absent or dead father might come with different consequences of how power is felt and experienced. It may or may not save the son from what I am about to say next.

The transition of a father back into their childhood is fraught with tension and conflict. The father has hardly known a bigger source of meaning than being a father and everything that comes with it. The transition starts happening when the son does not need the father to take care of him; it is almost as if the father is robbed of his meaning & purpose. The father also starts depending increasingly on the son for support and care, all the while hesitant to give away all the power he has. The son may not may not want the power but within the umbrella of patriarchy he can hardly ever avoid it. The ambivalence that is created between the father-son as both fights to maintain, gain or give up power leads to intrapsychic and interpsychic conflicts. This is hardly ever acknowledged.

The son also gains power from other sources such as Kratos did as he grew older. This ultimately leads to confrontation between father-son, although it may never be explicit in many cases and the anxiety takes the form of resentment. The son exercises his power to influence the father, someone so long only had influenced the son. A change in this dynamic is met with resistance. The father may continue to fight for his power, for to give up this power would mean giving up meaning, identity and strength. The anxiety would be: what would remain of them? While in other cases, the father might learn to be a father again; he may question and see what it means to be a father in this transitional time. This is where GoW helps us. Kratos was a son, and a father. He was a terrible father who killed his own wife and daughter. His father killed his father before him, and Cronos was so paranoid that he would eat his own children. The anxiety of meaninglessness, of being reduced to the shadows of nothingness is a perceived one, albeit real for the one experiencing it. But Kratos has been given a second chance, when he fathers Atreus. Kratos is protective, strong-willed and brave. He is the god of war after all. But what he also becomes is kind, caring, nurturing and sensitive. His protectiveness is not about rage and control, but rather about care and concern. By the end of GoW (2018), Kratos via Atreus has finally learned to forgive himself and accept himself for who he truly is. There is a juxtaposition of his Godhood and humaneness. He is a god filled with flaws, scars that remind him of his darker past; yet he is also a father who is learning from his mistakes, embracing the playfulness, and warmth his son Atreus teaches him.

I believe there is a Kratos in us all. Not the Kratos who kills Zeus, but the one who embraces Atreus, his boy. While a power struggle between father-son is unavoidable, it need not be fraught with conflict that involve intense intra & interpsychic challenges. It is important to acknowledge for the father that the only meaning & identity they hold is not one of power, and authority. There are more than breadwinners, and brave men that are supposed to protect us. Fathers are fallible, sensitive, and kind beings who can give themselves the opportunity to be a father again- of a different kind.

Identity is dynamic, and men are ascribed their identity. Patriarchy crumbles us as we grow older. The privileges that patriarchy presents us with can also be seen as double-edged swords responsible for the consistent internal conflicts we face within and outside. Power cannot be destroyed, but it can be contained. We need to reflect and see the strength of power itself. Power is exercised consciously through our actions, but moved by our unconscious. Identity is not simply rested on the power we yield or the roles we play; we are more than the sum of our actions. What we are is fallible humans who are ever changing and learning. A father is not just a father, while that might be the centrality of his identity; it is the father himself who has to give himself the chance to be more.

I acknowledge the irony of talking about the father while not being a father. Yet, I think Kratos learned to be a better father because he was a son first.

Learn MoreReflections on the privilege of grieving

Like many of us, school was not a very good experience for me. It always surprises me that the space where we spend most of our lives across multiple development stages is fraught with such threat & anxiety. I would find myself daydreaming, distracted or imagining scenarios that would never exist, and at times I would find myself soaked into certain proses from my English & Hindi textbooks. It’s surprising to many that I enjoyed the stories CBSE decided, and the context here is that I did not read a book until I was in 11th, so the only access to literature I had were my textbooks.

Adolescent Manish came across this Hindi prose called “Dukh ka adhikar”, and I distinctly remember crying as I finished the 4-page story. Something about the story stood out to me, and I guess presently as a therapist I can reflect upon & understand what about it was so powerful, and timeless.

The story

The author (Yashpal) talks about an old woman in white saree, sitting on the footpath trying to sell muskmelons. She has her head down on her knees and is sobbing, she lost her son yesterday. In the prose, you will find different characters commenting on the woman’s lack of dignity & integrity, how she started business so soon after her son died; all of them unaware of her predicament. The old woman has two grandchildren to feed and a widowed daughter-in law, but no money to buy food. Any little money that they had was used for her son’s last rites. An old grieving mother with no money, and voyeuristic people shaming her.

The author contrasts this with his neighbour who also lost her son last year; this lady was bed-ridden for months to grieve, she had access to doctors and caretakers round the clock. The author paints the picture of how she was allowed to grieve.

My reflections

Adhikar translates to right, and hence one can interpret the title as the ‘Right to Grieve’. I would like to interpret it slightly different, and use the word ‘privilege’, i.e., the privilege to grieve, to feel.

The prose very directly talks about class differences and how people belonging to certain class have the right or the privilege to grieve, whereas others have to ensure mouths are fed while being privy to society’s voyeurism.

As a therapist I actively encourage my clients to reflect, to feel their emotions as it is an important aspect in the process of healing. A few months ago, I started to realize that to feel, process and grieve is a privilege, a luxury if I may add. Majority of us do not have the space to feel our emotions; we are constantly demanded by external factors to perform, to be perfect, productive members of this voyeuristic society, that there is rarely any space to be human, to be devastated, imperfect and a mess. Just like the old woman in the story selling muskmelons to feed her family, many of us have roles & responsibilities that pressurize us to move on or supress our feelings: systems such as family, educational institutes, work etc. all contribute to this culture. It is a systemic flaw where we are expected to keep moving, hustling where stillness, to pause is seen as unproductive.

I use the term ‘voyeuristic society’ because all of us are so intrigued by others’ lives that we forget about our own self. Everyone feels too seen, alongside a weak sense of privacy and virtually no anonymity or personal space; we all see others and feel too seen ourselves that it creates a cycle of voyeurism that is often accompanied by judgement and shaming. We judge and shame others because we feel judged and shamed ourselves. It is a positive feedback loop that leaves no room for processing, feeling and just being.

I find myself telling clients I work with to pause, and I remind them that the second wave of covid-19 in the country was happening roughly 2 months ago, that is just 60 days or so. It is important for us to remind ourselves of streets in cities that became open crematoriums, we cannot forget that we were collectively mourning, in utter shock and perhaps despair. We cannot just move on.

The privilege to grieve is just as real and like any other form of privileges, it varies amongst us all. I think that many of us are so afraid of the collective shame, the voices of systems judging us that suppression seems to be the only way out. As a therapist, I am afraid too. What do we do when so many forces work together to ensure we don’t feel? More so, what can we even do when we ourselves are part of these forces. Who do we blame? Who do we hold responsible? It is complex of a process for any linear progress to happen.

My intentionality has been to recognize the privilege of feeling, to further the idea the author posits: we should all have the right to grieve.

I leave you with a line that stood out to me from the prose (forgive my poor translation): “A living man can bear to live naked, but how do you cremate someone who is dead, naked?” Loss & grief is complicated, and requires more from us than we can ever be prepared to imagine.

Lastly, with utmost vulnerability I must add: this was my attempt at processing pain.

Learn MoreWhy I disagree with the term ‘Toxic Positivity’

The current buzzword in the world of pop-psychology is ‘toxic positivity’. It is an effort to highlight the dangers of ‘good vibes only’, and how negative emotions cannot be avoided. I wholeheartedly agree with what the term stands for, but strongly disagree with the term ‘toxic positivity.’ For some, it might seem a mere semantic issue but I feel it is far more than that, and I shall try to elaborate how.

Toxic positivity has been defined as “the excessive and ineffective overgeneralization of a happy, optimistic state across all situations” (Quintero & Long, 2019). Simply, it is a state of denial and reaction formation and even the authors mentioned above acknowledge this: “process of toxic positivity results in the denial, minimization, and invalidation of the authentic human experience.” Clearly, what we understand as toxic positivity is simply ego defense mechanisms (if you subscribe to Psychoanalytic thought) or forms of contact (if you subscribe to Gestalt thought). The question arises then- how did this term gain such traction is the past 2-3 years? The answer perhaps lies in our fondness of the term ‘toxic’.

The word ‘toxic’ has gained colloquial relevance, we tend to use it to describe almost everything that we don’t agree with or the ones that make us feel uncomfortable. Statements such as “that person is so toxic”, “your relationship seems very toxic”, “what you are doing is very toxic” can be observed in everyday conversations. I feel it is important to acknowledge my stand on calling out unhelpful & unhealthy behaviors: It is necessary and people must be held accountable for their actions. My issue is not with calling people out as much as it is with the colloquial use of the word ‘toxic’ because certain thoughts, emotions and actions are actually dangerous, harmful, unacceptable & unpleasant but do all behaviors fall under this category? If we were to look at it from a reductionist and top-down approach, the answer would be a clear yes.

It is when we adopt a bottom-up approach with an attitude of curiosity and nuanced understanding of the other person, we tend to truly understand what the other person’s behavior signifies. To elucidate, if someone is saying “good vibes only”, is there a possibility that they are either using denial as a defense mechanism or resistance as their form of contact? Another person might be living in a family or a system that never encouraged emotional expression and thereby the only way they can make sense of their life (both good and bad) is to engage in certain forms of behavior that are not necessarily helpful (here: being unrealistically positive or in denial). A third person is actually working on their denial and resistance to authentic experiences, this process is not linear and they might go back and forth with denial. Do all these instances warrant ‘toxicity’? I think not.

Semantically and psychologically positivity is associated with hope, confidence and an experience of being in control. I recognize how hope, confidence and control can also be unrealistic but it definitely is not toxic. We need to draw a line between faulty perceptions of the self and labeling those faulty perceptions as toxic.

When we label attitudes and perceptions as toxic positivity, we might not be engaging in a helpful behavior ourselves. Labelling something as toxic is unfortunately the easy way, understanding requires nuance, curiosity and openness to challenging our own thought.

With advent of the pandemic, we have seen a lot of people on various platforms focus on ‘good vibes only’, ‘let us focus on the positive’, and ‘let us be grateful for what we have’ etc. I do not condone such statements as they are insensitive, unhelpful and ignorant. Despite that I will not call them toxic because insensitivity or ignorance does not necessarily mean toxicity. What it does mean is that there is a huge gap that needs to be bridged through dialogue and sensitivity, labelling is reductionist and arm-chair activism. Such insensitive comments are not simply about the handful of people who put it out but rather is symbolic of society at large- it is easy to find scapegoats for societal problems.

Imagine this scenario: A healthcare worker has been working very had with their covid-19 duties, is exhausted and on the verge of burnout. The same worker has a wallpaper on their phone that says: “good vibes only”, it is something they truly believe in, especially given the situation they are in. Is this healthcare worker spreading toxic positivity? No. Are they burned-out, lack skills for emotional expression, lack space to express and are overwhelmed with fear of judgement that ultimately leads to this form of contact? High possibility that is the case. In this example I am not encouraging ‘good vibes only’ attitude, I am acknowledging the possibility of nuance; my intention is for us to look beyond the obvious.

We have a big communication and emotional expression problem in our society, and the lack of safe spaces where we can express does not help either. Interpersonal communication is a skill that we are unfortunately not taught but rather suppression and denial is encouraged. Here again, I highlight a societal problem rather than an individualistic one, or those limited to only a group of people.

Lastly, I would like to acknowledge that it is not all of our duty to listen and attempt to understand the nuances of others’ way of being all the time; so many of us might not have the bandwidth for that. My intention here has been to demystify a colloquial use of a term which focuses on the peripheries of human behavior; to simply encourage (if you can) to look at each other beyond what is obvious.

We like to think we are conscious beings but a lot of what we do, say or feel is not so conscious. We are systemic humans after all.

References

Quintero, S., & Long, J. (2019). Toxic positivity: The dark side of positive vibes. The Psychology Group. Retrieved from https://thepsychologygroup.com/toxicpositivity/Learn More

Gulmohar Discussion Groups

Introduction

To those of you are familiar with us, it is no secret that we, at Gulmohar, love groupwork! Over the last few months, we have been running Weekly Discussion Groups as part of our response to the Covid-19 pandemic, on topics such as:

- Hope, Meaning and Despair

- Relationships

- The Experience of Artists (All of which are set in the Covid-19 context)

As we have found these groups to be a wholesome and fulfilling experience, we are very excited to open them up to all of you! The purpose of the groups we host is usually focused on creating safe spaces for conversation and deliberation about a topic at hand, and an opportunity for reflection with people.

We also find them to be a productive time of creating moments of shared experience and learning alike.

Some things to note about these discussion groups are:

- They are conducted online, usually on weekend afternoons with about 4-6 participants.

- The process of the group typically consists of the facilitators (us) asking the participants open-ended questions, that intend to stir reflection and awareness on the topics we cover. There is absolutely no requirement for preparation, or knowledge pertaining to the topic!

- These groups are meant to be safe spaces for thinking and sharing about your experience of things, in a hope of creating meaning, and feeling a sense of belonging.

- While there is a degree of structure- with rounds of questions being asked and rules in place to ensure safety and amicability, open expression of self is very encouraged.

- There is also no bar to entry. If our slots for the weekly discussion are full, hop onto the next one! We find each session to be rewarding and unique in what it provides.

If you are interested in participating in one of these groups, or would like to know more, email us at [email protected], or reach out to us through our instagram page (Instagram handle: gulmohar.mentalhealth). Hope to see you there!

Isolation, Love and Vulnerability…Connecting the dots

What is Loneliness?

Loneliness has been looked at differently by various schools of thoughts. It has been widely studied in philosophy and psychology; understood as “a state of solitude or being alone”, or as “a feeling of disconnectedness or isolation”.

Existential Isolation

The school of existentialism bridges the understanding of loneliness between philosophical and psychological schools. Yalom (1980) writes of existential isolation as “an unbridgeable gulf between oneself and any other being”. He contends that loneliness or existential isolation is an Existential Concern, i.e. a given of life and thereby is inescapable. Another researcher (Pinel, 2017) has understood it as individuals feeling alone in their life experiences, devoid of others who are able to understand their realities.

Nothingness and Maya

Yalom (1980) connects freedom, death, identity and meaning with existential isolation: articulating how a man is born alone and will die alone. He contends that we engage in the process of defamiliarization, in order to deal with the ultimate helplessness of being born in a world devoid of meaning, as we are ‘thrown’ (Heidegger, 1927) into being.

We tend to suppress experiences of isolation, an unwillingness to engage or explore. We may do so because we feel helpless, and thereby construct artificial environments and relationships to help deal with it. Heidegger has called this “uncanny (not at home)” to describe a world that has been created by mankind where it does not feel at home, i.e. an illusory environment- “Maya”. What guides humans to engage in this paradoxical exercise of free will is the fear of nothingness. As Heidegger said “Of what is man afraid? Of nothing!”

This experience of isolation is aggravated when we do not feel understood, or feel we are alone in our experience of isolation.

Love as a companion

Erich Fromm (1956) understands that aloneness causes anxiety, and how human action(s) is directed at alleviation of the anxiety we experience because of our isolated states. We strive to achieve this through love, but we are so fraught with Maya (we create artificial relationships with the illusion of intimacy) in love, that it takes us away from authentic intimacy. Simply put, Fromm states that our fear and anxiety of being alone dominates our actions aimed at achieving intimacy, and the anxiety is so dormant that we take solace in the illusion of love (Maya) than actual love itself, because the latter requires more effort and patience. For instance, we may engage in short-lived relationships devoid of commitment as real intimacy may seem daunting.

For Fromm, love is not in the material, but within ourselves. Authentic love lies in the act of giving, that of joy, interest, knowledge, understanding and sadness.Love is not about falling for but about standing in. The capitalistic structure that we live in, not only takes us farther away from self and intimate connections, but also creates a environment where individuals are more concerned with being loved rather than loving.He also warns us on how we deceive ourselves to think of certain relationships as intimate but they are peripheral and do not touch an individual’s core; for instance, symbiotic love is where individuals are enmeshed without respect for each other’s integrity, and individuals may not know ‘why’ they are together.

According to him, the economic system of capitalism influences our unconscious mind, our relationship with parents and God, who and how we love. This makes us feel unanchored and alone, alongside the debilitating uncertainty that existence befalls upon us, which ultimately leads to us forming shallow connections- this gives us a sense of control, vis-à-vis certainty.

Vulnerability as a facilitator

So if

- Existential isolation is inescapable;

- Authentic connection and intimacy can reduce the intensity of pain and helplessness in a meaningless world;

- But the broader capitalist structure ensures we engage in illusory and peripheral choices;

Then how do we bridge the gap between isolation and intimacy?

The answer lies in vulnerability. It is understood as “the core of all emotions and feelings” (Brown, 2012). What we are more afraid of is not the other (someone else) but the self (ourselves). A lack of vulnerability and authentic connection is not only reflective of one’s relationship with others but also of one’s relationship with one’s own self. Vulnerability as courage weighs in, is the facilitator in the oscillation between existential isolation and intimacy.

Vulnerability is a process

When we enhance vulnerability with ourselves, we begin to recognize the illusory and shallow connections we have made, and begin to accept this inescapable loneliness.

It is a process, and a difficult one- it begins with vulnerability with ourselves. It is when we dare to choose to see the real, and what has been missing, can we strive to come out of this Maya. To reiterate, disillusionment is a lengthy process, and looks different for all us, and it is in this process that we may begin to see subtle yet significant changes that take us closer to a more authentic, meaningful life.

Recognition and acceptance does not warrant freedom from existential isolation, rather it is in the acceptance of this state of being in which we can experience freedom. Vulnerability gives us the power to choose to feel connected, where genuineness and authenticity liberates us.

References

Brown, B. (2012). Daring Greatly. Penguin Life.

Fromm, E. (1989). The art of loving. New York: Perennial Library.

Heidegger, M. (1927). Being and Time. Taylor and Francis Ltd.

Pinel, E. C., Long, A. E., Murdoch, E., & Helm, P. (2017). A prisoner of one’s own mind: Identifying and understanding existential isolation. Personality and Individual Differences, 105, 54–63.

Yalom, I. (1980). Existential Isolation. Existential Psychotherapy (pp.353-346). United States of America: Basic Books.

Learn More

Suicide Prevention

Introduction

Suicide is the act of intentionally taking one’s own life. A person might resort to such an agonizing conclusion to their life because their experience of pain has become unbearable. Although most suicidal people feel deeply conflicted about ending their own lives, they just can’t find an alternate way to end the tremendous pain they are carrying. They see ending their life as the only option to escape their suffering, self-loathing, and isolation.

Risk Factors

The factors that might put someone at a risk of suicide include mental illnesses (such as Major Depressive disorder, Bipolar Disorder, Personality disorders, and Schizophrenia, among others); substance abuse and withdrawal, previous suicide attempts; and stressful life events and situations (such as bullying, harassment, domestic violence, poverty, breakups).

Consequences

Suicide leaves behind a trail of trauma, guilt, anger, and agony for those who witness such an abrupt end to their loved ones’ life. It is unfinished business that continuously gnaws at them and they are left grappling to somehow come to terms with what happened, and what they could have done to prevent it.

How can you help?

1. Recognize warning signs– This includes talking about killing or harming oneself, seeking out lethal means (such as gun, poison, rope…); preoccupation with death; hopelessness about future; self-loathing and self-hatred; self-destructive behavior; withdrawing from others and isolating oneself; saying goodbye to people which has a sense of finality to it; getting their affairs in order; and a sudden sense of calmness.

2. Talk to them if you feel worried- You might feel worried about broaching such a sensitive topic. You certainly don’t wish to offend them or make them feel judged. But remember, if you are worried for their well-being, the best way to find out what is going on, is to kindly and empathetically talk to them.

3. Being mindful while talking to them about their suicide intent:

Do’s

- Be yourself- It’s not about finding the right words but letting them know that you care for them, and that their life is valuable.

- Listen to them in a sympathetic and non-judgmental manner.

- Take them seriously.

- Offer hope- Let them know that help is available, that their suicidal feelings are temporary and that you are there for them.

Don’ts

- Argue with them- ‘How could you be so selfish? You are not thinking about your family members’.

- Promise confidentiality- Since you might have to disclose this information to relevant others. If your promise confidentiality and then break it, they might end up feeling betrayed by you.

- Try to ‘fix’ them- ‘Suicidal feelings and behavior are complex phenomenon, that require professional help. Taking it onto yourself to ‘fix’ or ‘save’ someone will not just be draining for you, but also counterproductive for them.

- Act shocked- ‘How could you talk like this. It’s immoral and irreligious to end your own life’.

- Blame yourself- You loved one’s happiness or lack thereof, is not your responsibility. Be supportive towards them, and make them valued and cared for, but do not blame yourself for the way they are feeling.

4. Evaluate the immediate danger they are in:

Following questions might help:

- Do you have a suicide plan? (PLAN)

- Do you have what you need to carry out your plan? (MEANS)

- Do you know when you would do it? (TIME)

- Do you intend to take your own life? (INTENTION)

Level of suicide risk:

- LOW- Some suicidal thoughts, no suicide plan. Says he or she won’t attempt suicide.

- MODERATE- Suicidal thoughts. Vague plan that isn’t very lethal. Says he or she will not attempt suicide.

- HIGH- Suicidal thoughts. Specific plan that is highly lethal. Says he or she will not attempt suicide.

- SEVERE- Suicidal thoughts. Specific plan that is highly lethal. Says he or she will attempt suicide.

5. Offering help and support:

- Get professional help- Suicidal thoughts, feelings, and behavior are a complex phenomenon that require professional attention. A combination of therapy and pharmacological help might alleviate your loved one’s suffering.

- If a suicide attempt seems imminent, call a local crisis center, remove lethal objects from the vicinity. DO NOT under any circumstances leave the suicidal person alone.

- If they are undergoing any treatment follow up on it- ‘Have you been going to therapy?’; ‘Have you been taking your medications?’

- Be proactive in providing them support and care- Do not wait for them to reach out to you. Call them, drop by, invite them for gatherings even if they said no last several times.

- Make a safety plan: Help them come up with a safety plan to be followed during a suicidal crisis. This could look like calling a local crisis center, calling friends, family or other relatives; distracting oneself. You could read more about safety plans here- (attach link)

- Continue your support over the long haul- This might be one of the most important things you could do for someone experiencing suicidal intent. Keep checking on them and letting them know you care, and that their life is valuable.

6. Lobby for responsible media reporting of suicide: Studies show that media coverage of suicide behaviors and actual suicidality are associated (Sisask & Varnik, 2012). There is strong modeling effect (learning by observation) seen in vulnerable individuals because of highly publicized reporting. Sensational reporting of suicide actually provokes suicidal behavior in those at risk. You could read about WHO Guidelines for responsible reporting of suicide here (attach link).

7. Lobbying for systematic changes aimed at suicide prevention- Macroeconomic policies aimed at meeting the basic needs and rights of the population (employment, healthcare, education, water, sanitation); organizing local support groups within vulnerable sections of the society; changing the culture which accepts suicide as a way out of misery; social justice efforts for minorities like women, Bahujan communities.

Note: Gulmohar does not provide suicide helpline/ intervention. Please call a suicide helpline number if you are in distress.

Suicide Helpline number: +91 9820466726, or visit http://www.aasra.info/helpline.html

Learn More

Group Work

Introduction

At Gulmohar, we believe in the enormous potential of Group Work in facilitating healing, learning and growth. We translate this belief into practice through our offerings of Therapy groups, Support groups, and discussion groups at our organization.

These groups are safe spaces for people to express themselves without judgement, share each other’s pain and joy, connect with like-minded people, and be challenged in their old and unhelpful ways of thinking, feeling and being.

Group Process

Purpose of the group

What goal do we wish to establish at the end of the group process?

Discussion groups. It could be facilitating discussion between group members on a particular theme, providing them with a safe space to express themselves, and to understand how others have been experiencing a similar situation. This could facilitate a meaning making process within each member of the group, and a sense of belongingness.

Support Groups. Alternatively, the purpose of the group could be to bring together people who are going through a similar experience (such as loneliness, trauma of abuse, anxiety). Group members draw comfort from knowing that they are not alone in their suffering, and find compassion, friendship, and understanding in people who truly understand their experience of pain.)

Group Therapy. In this, individuals receive therapeutic interventions in a group setting. Sometimes these groups have a theme (for example a therapy group for individuals who are experiencing identity distress). Therapy groups aim at helping the participants raise awareness about their experience, bring about changes in their life, and heal from their traumas.

Planning groups

We put in considerable time and effort in carefully planning these groups, as we base our planning in theory and research. After we have a layout of the plan ready, we consult with our mentors and get the content validated by them. We also pay heed to any suggestions, feedback or recommendations by them and make necessary changes.

Screening group members

The purpose of doing this is to ensure the benefit of the group at large. Through pre-session interviews we determine if a particular individual will be fit for that group. Say for example, a person is really overwhelmed, and requires a lot of individual attention by the therapist, in such cases, we would recommend that he/she seek individual therapy first.

Group Work commences

There are a lot of benefits that you can accrue from being a part of the group. This includes

- a feeling of universality– knowing you are not alone in your suffering);

- a sense of belongingness, emotional connectedness and acceptance- facilitated by coming in close, authentic contact with those who are experiencing problems similar to yours;

- an emergent sense of hope– when you see others grow and change, you might feel inspired and become hopeful about your own ability to change and grow.

- Feeling good about yourself- In a group setup, you not just receive help, but also provide help. You become a part of others’ journey of growth and healing. This might make you feel valuable, and boost your self-esteem.

- Emergence of interactional patterns– Groups act as a social unit where interactional patterns of the group members emerge. For example, you might become aware of your tendency to be judgmental; not give someone the benefit of doubt; be distrustful, cut someone off…

- And a safe place to constructively resolve conflict which carries over to your life at large: An environment of honesty and trust within the group allows for its members to effectively communicate with each other. It provides an opportunity to get in touch with your feelings, values, as well as baggage, and patiently process everything. This newfound way of communicating and being translates into life outside the group.

- Catharsis. As you narrate your experience, and get in touch with your feelings, in a safe, receptive environment, you can expect a sense of release and nourishment of the soul.

- Modelling adaptive behavior. When you witness other group members engage in adaptive behavior, you might feel inspired to do so too. For example, a group member who shows bravery and courage in showing disagreement with something that happened within the group, despite the fear of feeling like an outcast, might inspire others to be authentic and true to themselves, and voice their opinions more freely.

Termination of group

There is a bittersweet feeling when the Group Work comes to an end. There is a sense of loss for a space that had become a place of learning and healing for the group members. There is also a sense of achievement in the journey of growth and change that the group members embarked on together.

Learn More

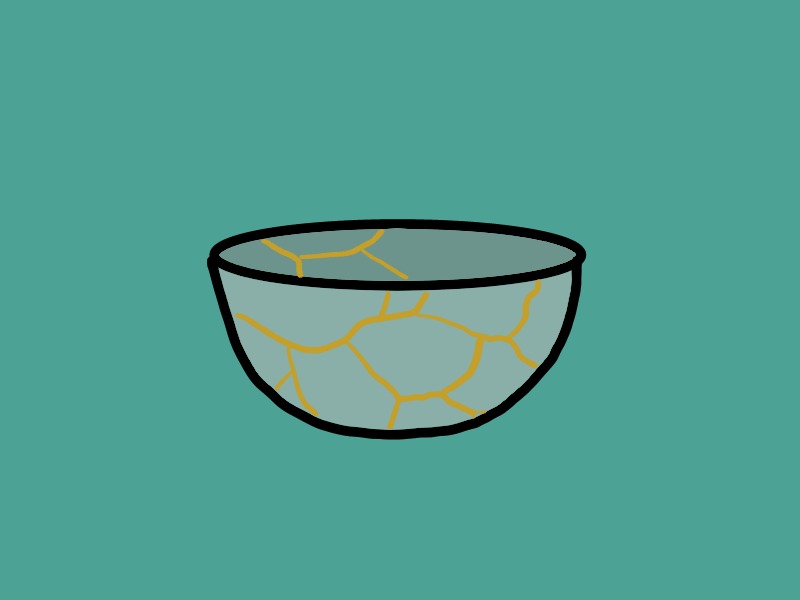

Kintsugi: A metaphor for Post-traumatic growth in today’s turbulent times

“There is a crack in everything, that’s how the light gets in“.- Leonard Cohen

How many of us can say that we have gone through life completely unscathed? The answer is none of us. It’s rather impossible to go through life- especially the thick of it- and not have picked up a couple of scars along the way. Nor is it unusual for us to try and hide our scars from others- or even from ourselves. But the truth remains that we all have cracks. Some that are tiny, some that are more mighty, some in places we cannot see, some that appear small on the surface but run deep, some we have forgotten about, and some which may consume us. Each of these cracks is a symbol of our shared humanity.

What is Kintsugi?

Kintsugi or kintsukuroi is a Japanese artform of repairing broken pottery- objects with cracks in them. Its traditional practice involves using a precious metal in liquid form or lacquer dusted with powdered gold to join broken fragments of an artefact to repair it. As a result, the object is transformed and even more stunning than before. This technique of mending broken objects thus emphasises and brings out the beauty in cracks, conveying in its essence, a message of resilience and the potential for growth even after damage.

How our cracks can be a source of growth (Post-traumatic growth)

Within the field of psychology, the concept of post-traumatic growth (PTG), developed by psychologists Richard Tedeschi and Lawrence Calhoun in 1996, has been understood as the positive change and growth that is seen in people who have endured psychological distress following adversity, upon having worked through the challenges and issues that arose as a result of having undergone trauma. In other words, it is the transformation a person goes through, by allowing their ‘cracks’ to be a source of new growth, ultimately enhancing their lives and the way they relate to themselves, others and the world around them. Though this process of facing our challenges, we may be changed in a way that is similar to how broken objects are transformed into refined artefacts through the art of kintsugi.

Moving forward in today’s times (Relevance in the Covid-19 context)

In recent times, we as a society have endured colossal blows to our health, economy, and welfare. Indeed, this has left its imprint on the face of humankind, leaving behind monumental cracks in world we live in. As we try to move forward, we simply cannot ignore these cracks or look past them. Nor would it be wise for us to aspire to ensure that everything is returned to the way it used to be- to the old normal-before crises struck. It is undeniable that these events and catastrophes that we have experienced over the course of the past year have certainly made their mark, and in doing so, have thrown some light on the major cracks that exist in our society (some of them which have been hiding in plain sight!), showing us how truly deep some of them run. Indeed, these alarming events have highlighted the areas and gaps which we need to attend to. It is by way of directing our time, energy and resources towards bringing about and implementing change in these areas, that we as a community may hope to transform into a more inclusive, just and sustainable society.

Sometimes, it takes adversity to draw us out of our comfort zones, push us to re-examine our views and choices, spring us into action and demand us to change. Let the damage that has been done to our world not be for nothing. Let us allow it to incite within us a burning passion to grow, to emerge from the ruins of our past and overcome the trials of circumstance. Let us accept responsibility for the well-being for our society, so that together- we may rise above our suffering and work towards building a better world for us all.

References

Tedeschi, R. G., Cann, A., Taku, K., Senol‐Durak, E., & Calhoun, L. G. (2017). The posttraumatic growth inventory: A revision integrating existential and spiritual change. Journal of Traumatic Stress, 30(1), 11-18.

Learn More