Isolation, Love and Vulnerability…Connecting the dots

What is Loneliness?

Loneliness has been looked at differently by various schools of thoughts. It has been widely studied in philosophy and psychology; understood as “a state of solitude or being alone”, or as “a feeling of disconnectedness or isolation”.

Existential Isolation

The school of existentialism bridges the understanding of loneliness between philosophical and psychological schools. Yalom (1980) writes of existential isolation as “an unbridgeable gulf between oneself and any other being”. He contends that loneliness or existential isolation is an Existential Concern, i.e. a given of life and thereby is inescapable. Another researcher (Pinel, 2017) has understood it as individuals feeling alone in their life experiences, devoid of others who are able to understand their realities.

Nothingness and Maya

Yalom (1980) connects freedom, death, identity and meaning with existential isolation: articulating how a man is born alone and will die alone. He contends that we engage in the process of defamiliarization, in order to deal with the ultimate helplessness of being born in a world devoid of meaning, as we are ‘thrown’ (Heidegger, 1927) into being.

We tend to suppress experiences of isolation, an unwillingness to engage or explore. We may do so because we feel helpless, and thereby construct artificial environments and relationships to help deal with it. Heidegger has called this “uncanny (not at home)” to describe a world that has been created by mankind where it does not feel at home, i.e. an illusory environment- “Maya”. What guides humans to engage in this paradoxical exercise of free will is the fear of nothingness. As Heidegger said “Of what is man afraid? Of nothing!”

This experience of isolation is aggravated when we do not feel understood, or feel we are alone in our experience of isolation.

Love as a companion

Erich Fromm (1956) understands that aloneness causes anxiety, and how human action(s) is directed at alleviation of the anxiety we experience because of our isolated states. We strive to achieve this through love, but we are so fraught with Maya (we create artificial relationships with the illusion of intimacy) in love, that it takes us away from authentic intimacy. Simply put, Fromm states that our fear and anxiety of being alone dominates our actions aimed at achieving intimacy, and the anxiety is so dormant that we take solace in the illusion of love (Maya) than actual love itself, because the latter requires more effort and patience. For instance, we may engage in short-lived relationships devoid of commitment as real intimacy may seem daunting.

For Fromm, love is not in the material, but within ourselves. Authentic love lies in the act of giving, that of joy, interest, knowledge, understanding and sadness.Love is not about falling for but about standing in. The capitalistic structure that we live in, not only takes us farther away from self and intimate connections, but also creates a environment where individuals are more concerned with being loved rather than loving.He also warns us on how we deceive ourselves to think of certain relationships as intimate but they are peripheral and do not touch an individual’s core; for instance, symbiotic love is where individuals are enmeshed without respect for each other’s integrity, and individuals may not know ‘why’ they are together.

According to him, the economic system of capitalism influences our unconscious mind, our relationship with parents and God, who and how we love. This makes us feel unanchored and alone, alongside the debilitating uncertainty that existence befalls upon us, which ultimately leads to us forming shallow connections- this gives us a sense of control, vis-à-vis certainty.

Vulnerability as a facilitator

So if

- Existential isolation is inescapable;

- Authentic connection and intimacy can reduce the intensity of pain and helplessness in a meaningless world;

- But the broader capitalist structure ensures we engage in illusory and peripheral choices;

Then how do we bridge the gap between isolation and intimacy?

The answer lies in vulnerability. It is understood as “the core of all emotions and feelings” (Brown, 2012). What we are more afraid of is not the other (someone else) but the self (ourselves). A lack of vulnerability and authentic connection is not only reflective of one’s relationship with others but also of one’s relationship with one’s own self. Vulnerability as courage weighs in, is the facilitator in the oscillation between existential isolation and intimacy.

Vulnerability is a process

When we enhance vulnerability with ourselves, we begin to recognize the illusory and shallow connections we have made, and begin to accept this inescapable loneliness.

It is a process, and a difficult one- it begins with vulnerability with ourselves. It is when we dare to choose to see the real, and what has been missing, can we strive to come out of this Maya. To reiterate, disillusionment is a lengthy process, and looks different for all us, and it is in this process that we may begin to see subtle yet significant changes that take us closer to a more authentic, meaningful life.

Recognition and acceptance does not warrant freedom from existential isolation, rather it is in the acceptance of this state of being in which we can experience freedom. Vulnerability gives us the power to choose to feel connected, where genuineness and authenticity liberates us.

References

Brown, B. (2012). Daring Greatly. Penguin Life.

Fromm, E. (1989). The art of loving. New York: Perennial Library.

Heidegger, M. (1927). Being and Time. Taylor and Francis Ltd.

Pinel, E. C., Long, A. E., Murdoch, E., & Helm, P. (2017). A prisoner of one’s own mind: Identifying and understanding existential isolation. Personality and Individual Differences, 105, 54–63.

Yalom, I. (1980). Existential Isolation. Existential Psychotherapy (pp.353-346). United States of America: Basic Books.

Learn More

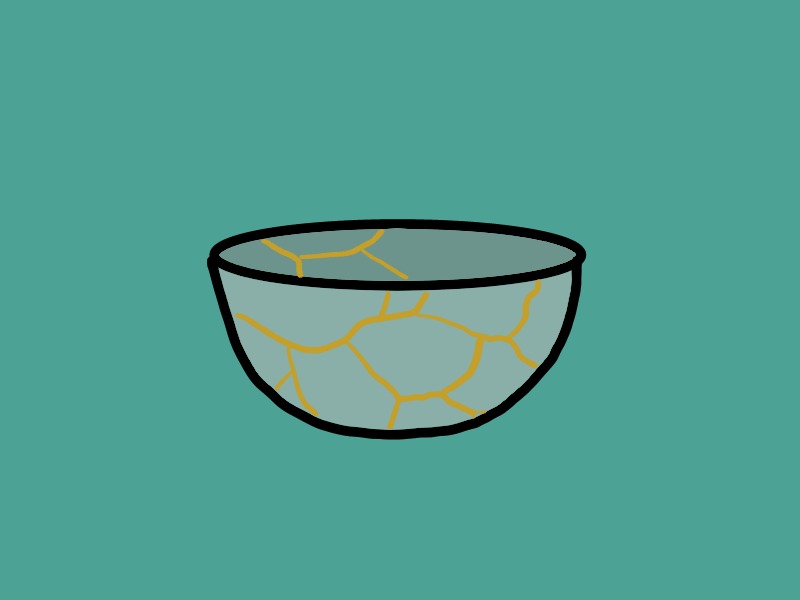

Kintsugi: A metaphor for Post-traumatic growth in today’s turbulent times

“There is a crack in everything, that’s how the light gets in“.- Leonard Cohen

How many of us can say that we have gone through life completely unscathed? The answer is none of us. It’s rather impossible to go through life- especially the thick of it- and not have picked up a couple of scars along the way. Nor is it unusual for us to try and hide our scars from others- or even from ourselves. But the truth remains that we all have cracks. Some that are tiny, some that are more mighty, some in places we cannot see, some that appear small on the surface but run deep, some we have forgotten about, and some which may consume us. Each of these cracks is a symbol of our shared humanity.

What is Kintsugi?

Kintsugi or kintsukuroi is a Japanese artform of repairing broken pottery- objects with cracks in them. Its traditional practice involves using a precious metal in liquid form or lacquer dusted with powdered gold to join broken fragments of an artefact to repair it. As a result, the object is transformed and even more stunning than before. This technique of mending broken objects thus emphasises and brings out the beauty in cracks, conveying in its essence, a message of resilience and the potential for growth even after damage.

How our cracks can be a source of growth (Post-traumatic growth)

Within the field of psychology, the concept of post-traumatic growth (PTG), developed by psychologists Richard Tedeschi and Lawrence Calhoun in 1996, has been understood as the positive change and growth that is seen in people who have endured psychological distress following adversity, upon having worked through the challenges and issues that arose as a result of having undergone trauma. In other words, it is the transformation a person goes through, by allowing their ‘cracks’ to be a source of new growth, ultimately enhancing their lives and the way they relate to themselves, others and the world around them. Though this process of facing our challenges, we may be changed in a way that is similar to how broken objects are transformed into refined artefacts through the art of kintsugi.

Moving forward in today’s times (Relevance in the Covid-19 context)

In recent times, we as a society have endured colossal blows to our health, economy, and welfare. Indeed, this has left its imprint on the face of humankind, leaving behind monumental cracks in world we live in. As we try to move forward, we simply cannot ignore these cracks or look past them. Nor would it be wise for us to aspire to ensure that everything is returned to the way it used to be- to the old normal-before crises struck. It is undeniable that these events and catastrophes that we have experienced over the course of the past year have certainly made their mark, and in doing so, have thrown some light on the major cracks that exist in our society (some of them which have been hiding in plain sight!), showing us how truly deep some of them run. Indeed, these alarming events have highlighted the areas and gaps which we need to attend to. It is by way of directing our time, energy and resources towards bringing about and implementing change in these areas, that we as a community may hope to transform into a more inclusive, just and sustainable society.

Sometimes, it takes adversity to draw us out of our comfort zones, push us to re-examine our views and choices, spring us into action and demand us to change. Let the damage that has been done to our world not be for nothing. Let us allow it to incite within us a burning passion to grow, to emerge from the ruins of our past and overcome the trials of circumstance. Let us accept responsibility for the well-being for our society, so that together- we may rise above our suffering and work towards building a better world for us all.

References

Tedeschi, R. G., Cann, A., Taku, K., Senol‐Durak, E., & Calhoun, L. G. (2017). The posttraumatic growth inventory: A revision integrating existential and spiritual change. Journal of Traumatic Stress, 30(1), 11-18.

Learn More